Creating slow-release, high-tech healing gels

Professor Sias Grobler and his international collaborators have developed multifunctional healing gels for dentistry and other applications. Image by ScienceLink.

For African healers that have used honey to treat burn wounds for thousands of years, it would come as no surprise that this

delicious, viscous pancake topping has been proven to have anti-bacterial,

anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties. It also sticks to a wound, creating an effective seal against infection.

Inspired by humble honey, scientists are looking for multifunctional wound gels among biological polymers known as hydrogels.

Professor Sias Grobler of the Oral and Dental Research Institute at the University of the Western Cape, along with Professor Tamara

Perchyonok in Australia, is investigating the ability of hydrogels to transport different compounds of medical and dental importance,

in much the same way that honey can carry anti-oxidants.

Grobler and his collaborators primarily work with a biopolymer called chitosan, which is harvested from the shells of shrimp, prawns

and other crustaceans. Chitosan is already widely used in various other industries: in winemaking it serves as an antifungal agent, in

agriculture as a growth stimulator, and it forms part of some protective paint coatings.

In the medical world, chitosan has been used as an antibacterial agent, as a source of soluble dietary fibre and in bandages to reduce

bleeding. Now Grobler wants to use it as a novel carrier of chemicals that need to be released in a controlled way.

“The problem with your usual injection is that it’s there now and then it’s gone. Chitosan on the other hand, releases

compounds over time – it’s a slow release, at a nice concentration, and over a long period.”

Chitosan does this by being a very good carrier under the right conditions. In a mildly acidic environment, it is positively charged,

which essentially means it binds very well to skin and teeth, as well as to other molecules added to it.

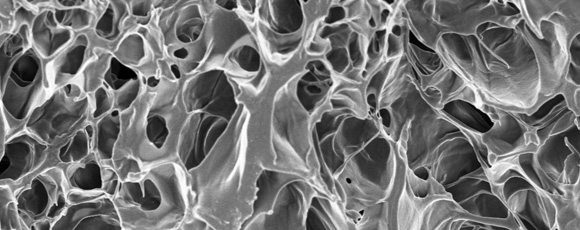

An electron micrograph showing the sponge-like structure of a chitosan hydrogel. Image courtesy of Sias Grobler.

“Chitosan can swell. It’s like a gel or grease, but it swells as soon as it comes into contact with water, and that allows chemicals

to move in.” So it works a bit like a sponge, sucking up liquid along with anything dissolved in it.

Grobler and a team of researchers based in Australia and China have tested chitosan extensively as part of multifunctional fillings for teeth.

For example, they have incorporated antioxidants, painkillers, propolis (a resinous substance produced by bees with many health properties),

nystatin (an antifungal compound) and even beta-carotene (a common plant pigment with anti-cancer properties) into the hydrogels.

They found that some of these multifunctional hydrogels bonded strongly with dentine (the soft part under the enamel in teeth) over more than six

months, and gave a slow, controlled release of the compounds mentioned above.

“We saw that when you add chitosan to the bonding agent, it increases the bond strength and keeps that strength over a longer period,”

he explains.

Of particular interest is that there is no need to etch the tooth before bonding. “In the past, dentistry has relied on phosphoric acid

etching (many researchers see this as a very destructive step) before dentine bonding. This is now unnecessary; we have shown that we don’t

need it. You can get the same or better bond strength with no etching.”

The group has also shown that many of the chitosan hydrogels have no toxicity to human pulp cells (the living, sensitive part of the tooth) and

chitosan in itself was found to increase the cell survival rate. This, says Grobler, is an extremely important step towards using chitosan hydrogels

for dentistry.

He adds that theirs is cutting-edge research, and they are some of the only people working on hydrogels for dental use. However, there are a few

groups investigating another biopolymer called cyclodextrin for the controlled delivery of drugs taken orally.

Academic journals such as the prestigious Journal of Dental Research have contacted Grobler and his group to request articles for publication,

which shows that this research is garnering worldwide academic interest.

With that in mind, is there any plan to commercialise the research? Not at this stage, says Grobler. “No patenting plans as yet – we want to

take the research further.”

Chitosan has not been approved by the FDA as drug carrier but has been approved in some combinations for wound healing. This would make pursuing

commercialisation extremely time-consuming and expensive, with no final guarantee of approval.

Nonetheless, it is an exciting avenue of research, and Grobler is visibly enthused when he talks about it. His excitement is justified: a

multifunctional binding agent that can release chemicals in a controlled way has the potential to revolutionise the medical world.

Professor Sias Grobler

is Director of the Oral

and Dental Research Institute at the University of the

Western Cape.

|

|